Some people set out to make history;

many others found themselves actively shaping it, often unbothered, or totally

oblivious of it. But a faithful ingredient in a historic feat or moment will be

an extraordinariness of some sort, a defiance of the norm and the presence of

unusual valiance or brilliance. It could be for the good.

Some people set out to make history;

many others found themselves actively shaping it, often unbothered, or totally

oblivious of it. But a faithful ingredient in a historic feat or moment will be

an extraordinariness of some sort, a defiance of the norm and the presence of

unusual valiance or brilliance. It could be for the good.

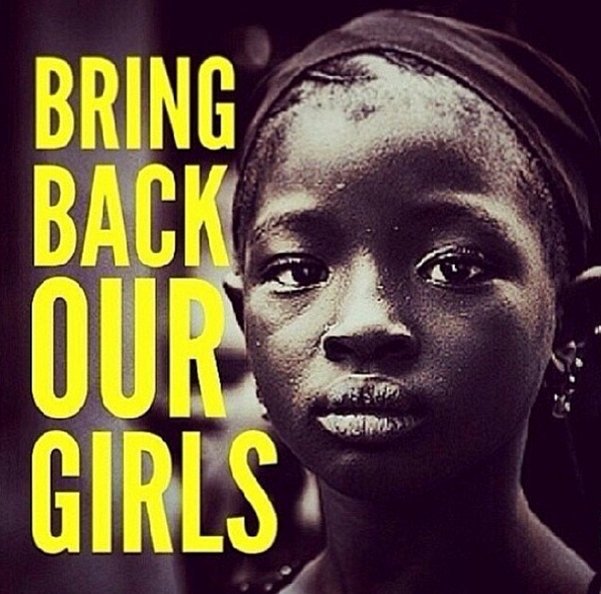

In the case of the viral

#BringBackOurGirls advocacy, the valiance of the women and men who heeded the

call of humanity in the days after the abduction of 276 girls from Government

Day Secondary School, Chibok, Borno State, on 14th April 2014, stood out and

effectively saved the soul of the Nigerian nation from self-immolation.

Yes, we saved the soul of the nation

from smothering its spirit of compassion, through what seems like a state led

disinterest in the suffering of folks whose cries are too far off to force us

to halt. We stood up and stared down the monsters of administrative lethargy

and irresponsiveness, at a time the sociopolitical odds were stacked against

us.

In building an empathy bridge to the

pain of the Chibok Parents and their community, and wearing their shoes of

agony, we found ourselves. We found our why and, decided we were not going to

back down. We found compatriots and comrades the world over. Our cause for the

rescue of the remaining Chibok Girls, after 57 escaped from the abductors,

found allies in the global media. The global media’s persistence also found a

ready ally in us.

We found admirers and won hearts.

Our candor also unleased hatred and cynicisms from many who desperately wanted

the abduction to be untrue, majorly because it hurt their politics or ruffled

their stereotypes. By placing the monstrosity of the abduction side by side

with the viciousness of the Islamic sect, the force of virality was triggered.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Nigeria is a paradox. The sociology

of our society is skewed against the poor and the weak. No one hears you unless

you get rich somehow or get very angry. The parents of our Chibok girls are

rural folks just like the parents of other victims from Buni-Yadi, Guljuba and

Dapchi in Yobe state. If the media had not beam light on their tragedies

and civil society groups not amplify their cries to the public, their

adversities would never have gotten assessed and efforts made at redress. The

success of the BBOG Advocacy was wrapped in fate, humanity and its courage. The

discipline and consistency came later.

The Boko Haram insurgency is

embedded in an extreme socioreligious doctrine that forbids formal education

and attempts to enforce Islam on a multi-religious, but officially secular

state. The first BBOG March of April 30th, 2014 was not a big bang. It

was the culmination of compounded frustrations of many weeks and months, over

government’s ineptitude and tragic incompetence in the handling of the

self-instigated Boko Haram insurgency. It was a calamity foretold.

It was a disaster we dished to

ourselves. A dreaded sect leader was arrested alive and handed over to the

Police and the next time he was seen, his body was riddled with bullets. The

trial of the five alleged killer policemen dragged on for more than six years

before getting thrown out for lack of evidence by the courts, like almost all

high-profile corruption cases in Nigeria.

The gory, brutal and horrific were

becoming our normal and, this was worse in the northeast particularly. Many

schools had been attacked or closed. Scores of teachers and school children had

been gruesomely murdered by the sect. The headquarters of the Nigerian Police

in Abuja had been bombed. The Nigerian UN Office in the same city also turned

up an easy pick for the Boko Haram. Nigeria found herself in the middle of a

suspense movie.

It was like ‘Homeland’ playing out.

Suicide bombers were on the loose on markets, worship centers and motor parks.

The militarization of our roads and cities was full circle. It was like a war

situation. I usually tell the awkward story of my visit to a UN Office in the

sub-region and the insecurity I felt as we go from place to place because of

the absence of heavily armed soldiers and sandbagged check points on the roads

in that country. The constancy of tension across Nigeria had practically

altered my psyche and what I considered safe.

It was a matter of time. Our

threshold was going to snap at some point. Parents were beginning to get

worried. Students were agitated and confused. The diplomatic corps readjusted

their reality from amber to red. Our political leaders were as unnerved as they

were clueless. The executive neither acted on or trust in its own intelligence.

It shamefully became the peddler of conspiracies about the insurgency. The

legislative arm of government was more concerned about personal monetary

enhancements.

Not a single public hearing has been

conducted specifically on the Boko Haram crisis by our National Assembly. Not

one either on the military arms procurement scandals. When they needed to step

up and align with Nigeria, they always choose closed door meeting with the

actors, who later turned out to have raped us blind through the corrupt

diversion of the funds meant to fight the war. I might have to return to the

shameful role of our Government in another article. This one is about the

#BringBackOurGirls Advocacy. It is about its perceived successes and failures.

It is meant to start reflections and inquisitions as the advocacy clocks four

years. This is not a love letter.

IS THE BBOG

ADVOCACY A SUCCESS?

The answer will be a runaway Yes,

within certain parameters. It is a self-validating fact. I will highlight the

reasons. To a great extent, the Chibok Girls abduction could have been swept

under the rug, like so many cases of abductions before it, by a government

desperate for reelection. The BBOG shined the light in a dark room and the muck

and mire became visible. The squalidness of the room appeared, and questions

arose to why they were so, even in the presence of a paid cleaner with all

necessary tools. What I am saying is that someone was on duty and the ship went

adrift. The BBOG group challenged the government’s reckless inaction, complicit

doubt and criminal insincerity.

I am a member of the movement. I was

there from the beginning. I was part of the online outrage and among the

‘sneakers on the ground’ in Abuja. The compassion was real. The anger was

fierce. The sight of all the women standing in the rain with the then Senate

President and Speaker on the very first march on April 30th, 2014 was humbling.

Not one person on that day would have been certain that the advocacy would

still be on four years later.

Despite the hostilities from

government, the movement grew stronger. We rallied together a nation that was

losing the essence of her shared humanity and compassion, the spirit of that

basic mutuality in the experience of tragedy. If only you considered the fact

that the attacks on schools started with a certain Success International

Private School in Maiduguri on July 29th, 2009, it would become clearer to you

how long Boko Haram had been out there burning down our schools and killing our

children.

Six classrooms and one school office

were razed on that day. That was almost 57 months before GSS Chibok abduction

happened. Attacks went on and on. From the very first attack on a school to

Chibok and till date, more than 1,400 schools have been destroyed or closed.

Very few people remembered that

Zanna Mobarti Primary School in Damasak had over 300 children between the ages

of 7-15 years abducted by Boko Haram when the Multinational Joint Task Force

were closing in on them in November 2014. Do you know that hundreds of teachers

had been killed before Chibok? The 2016 Report by Human Rights Watch puts the figure

at over 2000. Do you know that hundreds of innocent young girls from

communities were taken before Chibok? Where was the outrage? Where were the

sustained cries of the people so oppressed?

How far did our NASS proceed with

the motions of urgent national importance? What happened to the Governors and

elected officials of the region? They all chose politics except for one that

was later removed by the Government of the day, over a petition that made both

credible and fantastic claims.

BBOG restored our voices and

empathy. The movement’s Daily Sitout provided the balm for our injured nation.

Indigenes of the states in the northeast and Nigerians found a place where they

could ventilate in the Unity Fountain. No normal day ends without tears and

wailings.

The advocacy was a revolution been

televised to some and being lived by others. To the extent that we restored the

humanity of our nation, in spite of the jeers and sneers of the naysayers; to

the extent that we forced an initially lethargic and doubtful government into

action, whereby it started reaching out through multiple parties for a

negotiated release even if unsuccessful; to the extent that we kept the issue

of the abductions alive through one administration to the other, consequently

leading to the return of 107 out of our 219 daughters held in captivity; and,

to the extent that the light of the advocacy was a contributory factor to the

electoral defeat of the administration that supervised the abduction, the

#BringBackOurGirls advocacy succeeded.

But was that all that was possible

or that we could have done? The answer to this question leads automatically to

the next phase of my writing.

COULD THE

BBOG HAVE ACHIEVED MORE? WHAT STOPPED THE MOVEMENT?

Despite our successes, the

conversation about the scale of what the BBOG could have achieved, when the

lights were turned on, is yet to cease. It still goes on when activists sit

together locally and internationally. There have been many academic inquisitions

into the movement. There are valid opinions and misconceptions about our

approach and style of engagement, that seems to isolate friends and family

alike. There are hardline haters as well, who are incapable of accepting the

good and positive about a revolutionary advocacy.

One critical sentiment I have

encountered are those that see our Movement as antagonistic and, downright

belligerent. Some people kind of get the feeling that we would start a mass

brawl at a funeral, damning the solemnity. A lot of folks wonder if we wanted

more than the girls. And, that goes to the heart of a controversial concept

within the movement on where we should be; stand at the door or sit at the

table. It is a metaphorical inference to confrontation or collaboration.

At what point in civil activism and

advocacy should one fold up and leave or evolved? At what point should

persistence be the only strategy? At what point should messaging change? At

what point is tactical reinvention non-negotiable? At what point does street protests

become a nuisance? If messaging is important, what about language? You can be

sure there is no single answer to all of these.

Many other people also think that

our apolitical claim is a song we sing but don’t dance to. We are perceived as

having a grudge fight with the government and identifying with everything that

makes it look bad, thereby blurring the lines of our advocacy. Some of the

folks who work for the present government, like their predecessors, think that

we are in bed with the opposition, or see us as the new rallying army of the

mystical third force. No matter where one swings here, it is hard to wean

people off selective perception, especially when the trigger is personal.

This applies both ways, to the

movement and the critics. I have met some parents of our Chibok Girls who

resolutely affirm that they do not want the government to forget their children

in captivity, but also do not want to appear adversarial. They believed that no

one else can get their daughters back, and they are right. It is the reason why

some don’t like identifying publicly with us, even with their unreserved

admiration.

Another perception is that our vow

of singularity of purpose is myopic and self-serving. It is usually backed with

the repulsion a capitalist feels towards an investor who is served with China

on a platter but goes for Bangladesh instead. What I mean here is the fact that

we are perceived to have been presented with the opportunity window to lead and

drive the changes that Nigeria deserves aftermath of the 2014 abductions. If

you widen the connected issues, you will walk into the space of social

development, security reforms and public accountability.

Why is our military unable to end

the insurgency despite the massive growth of the security budgets over the

years? With the humongous expenditure, why do we struggle to adequately cater

for the welfare of the lower rungs of the military? How do we treat the

families of our fallen heroes from this war? What are we doing as a nation to

address the terrible yet growing inequality in the country? How can we

depopulate the recruitment line of Boko Haram through job creations or social

security? Why is corruption in the military treated with kid gloves?

Who is being prosecuted for corrupt

enrichment in the many reports of ghost soldiers and policemen in the forces?

What about the arms procurement scandals? The underlying fact of this is that

we have lost too many innocent lives and soldiers defending our country, not to

ask questions. And, I must say that we have been asking these questions. The

point now is the manner and approach. Are we compelling enough? Are we

strategic enough? Are we pressing the right buttons?

If you deepen the issues around the

Chibok abductions, you will be effectively faced with the state of education,

in quantitative and qualitative terms and, the hostilities the girl child faces

in the north of Nigeria. Where is the plan to reform a society that permit 13

years old girls to be married off? Is the Safe School Initiative enough to plot

our way out of the precarity we have created for schools in the north? What is

the state of its implementation?

Talking about the poor indices from

the northeast and northwest will be a rehash of the obvious. What is the plan

to raise enrolments? What is the plan to secure existing schools? I have been

to schools in southern Borno where teachers come armed to the class, just so

they could protect the pupils and prevent possible abductions. A friend accused

us in the BBOG as partly to blame for the Dapchi abduction because we were

fixated on the Chibok Girls and not raising enough dust on the porosity of

security around schools in the region.

Some people think we should have led

the establishment of a security protocol for boarding schools in the country.

They are not wrong. But it is not that uncomplicated.

Still on the singularity thingy,

many people I have encountered think it is an insensitive posture to adopt,

considering the scale of our complex emergency in the northeast. In the region,

a lot of people and victims of the conflict, see our advocacy as insensitively

obsessive about the return of the Chibok Girls, when there were over two

million internally displaced persons, many thousands of traumatized widows,

tens of thousands of orphaned children, prolonged lack of access to basic

education and a raging acute food insecurity to complete the nightmare.

AND WHAT

NOW?

Someone once asked me why we were so

angry without a plan. The truth is that we HAD a Plan. Though, the ship has

long sailed off on the fundamentals of that plan, I can attest confidently to

the fact that the plan was neither The Third Force nor The Red Card. It was

called the BBOG Strategic Plan. At least, for the Abuja movement.

We disagreed internally on many

things, but not on one key issue; zero political posturing. We were not to

bring the toxic politics of the polity into the movement. We were not to wear

political hats when we are on our saddle. We believed political coloring drowns

advocacy purposes in non-political causes. I think we did well initially. Some

people argue now that these are not normal times. But my take is that we have

braved worse seasons. Voices from within also called for us to pursue other

connected causes, but we resolved to stick to a singular purpose, which was the

rescue or safe return of our Chibok Girls. How well that served our cause or

providence is debatable.

Along with two friends, I took up

interest in the plight of IDPs with vigor. And, a lot of other people were

encouraged to pursue their causes. There are members of the movement working

with Almajiris, Women, Youths and Entrepreneurs. Some advocate for Girl Child

causes, some are fighting to fix Gender Based Violence and redress our poor

Gender Parity across sectors. Another friend has been working in the education

sector and some have pushed the frontiers of the state to develop a Missing

Persons Register. We have not done badly. I have friends who felt we lacked the

muscles to drive the connected issues. But, I know too well that you grow when

you stick to it. Then, the world would take note.

We disagreed also on whether we

should open the movement up to receive external funding, but the nays had it. I

was a ‘nay’. The external environment was too toxic then. Mudslinging was a

popular sport for the political jobbers. It still is. We would also have been

required to register as a non-governmental organization, create a formal

structure and codify certain rules into a constitution, propositions which

could not win with most of us.

We felt that could easily play us

into the hands of a hostile government. We however registered the Trademarks.

Another combustible issue we had to deal with was our language and messaging.

We strived to control our narratives by pulling down abusive and unconnected

placard messages during our marches and protests. We were sure of our mission.

It was not about the President. It was about the insurgency and the abduction.

On language, it was made clear to all never to call the President names and

mouth insults.

Civility was an obligation imposed

on every speaker at the Sitout. It was not totally successful. So, we created a

set of Core Values acronymized into HUMANITEEDS. The process to this point was

as good as the culture it birth, for a while.

The decision-making process in the

movement was the biggest elephant in the room. Writing about it would take a

book. I might give it a shot in the future. The evolution of that process was

topsy-turvy. Sometimes, it was a smooth sail. At other times, it was

acrimonious. I think it is a challenge many organizations or coalitions face. I

was convinced that the Government of the day, at the time, hated us and

desperately wanted to crush us. They rented crowds.

They deployed the Police.

Ironically, they also deployed thugs to unleash violence on us. The animosity

was palpable. But the animosity within the movement was fiercer. Distrust was

rampant. It is a reason why the numbers have dwindled, if you were ever

wondering. People were hurt. Sensibilities were offended. Egos were bruised.

Some people are still in their trenches, while others have moved on. It could

be an epic on how not to lead a movement. The sunny side to all these are the

lessons we have learnt and are still learning. Only few MBA programs could be

so impactful.

If this fourth-year introspection

forces many to write and share their views, the world of active citizens would

be blessed, and advocacy groups would be enriched. Many others would learn the

paths that should see less travels, how not to do some stuffs and vice versa. The

crowning glory of every protest and advocacy must be to succeed in changing a

culture that is no longer fit for an age; to force new conversations and

actions and puncture the bubbles political leaders live in; to amend unfriendly

or unjust laws so that a generation coming, or present will be free from the

shackles of an oppressive system, and to effect change.

The ‘Violence Against Persons’ law

was the crowning glory for a collaborative few who persisted. The ‘Not Too

Young To Run Bill’ is a great outcome for an adorable group who shook off the

shackles of oppression. The Nigerian Senate Public Hearing on the Migrants

Crisis in our backyard is also a fruit of a well channeled anger. If activism

fail to yield change, we may need to call Mama Winnie to give us a sign for

what to do with it.

OLATUNJI ‘LANRE-BARUWA

+2348092000444

@ola2njee

Ola2njee@live.com

No comments:

Post a Comment